Related

Guests

- Manning Marablelate professor of public affairs, political science, history and African American studies at Columbia University in New York City. He was the author of many books, including the just-published Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention and Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America’s Racial Future.

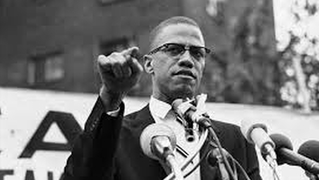

Renowned African American historian Manning Marable passed away on Friday at the age of 60, just days before the publication of his life’s work, a monumental biography about Malcolm X. Two decades in the making, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention is described as a reevaluation of Malcolm X’s life. We play excerpts from when Amy Goodman interviewed Marable in 2005 and 2007 about the chapters missing from Malcolm X’s autobiography and the groups implicated in his assassination. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: Renowned African American historian Manning Marable passed away on Friday at the age of 60, only days before the publication of his monumental biography of Malcolm X. Marable suffered for 24 years from an inflammatory lung disease and had a double lung transplant in July. He died of complications from pneumonia.

Marable devoted his life to writing the definitive biography of the civil rights icon. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention is published today by Viking. Two decades in the making, the nearly 600-page biography is described as a reevaluation of Malcolm X’s life, providing new insights into the circumstances of his assassination, as well as raising questions about Malcolm X’s autobiography.

Marable was professor of public affairs, history and African American studies at Columbia University. He founded and directed the Institute for Research in African American Studies. He authored several texts and was active in progressive political causes.

Marable appeared on Democracy Now! in 2005 and again in 2007 to discuss his life’s work and the biography of Malcolm X. We’re going to turn to excerpts from those two appearances. Marable talks about the missing chapters from Malcolm X’s autobiography and the groups implicated in his assassination.

MANNING MARABLE: I think that Malcolm X was the most remarkable historical figure produced by Black America in the 20th century. That’s a heavy statement, but I think that in his 39 short years of life, Malcolm came to symbolize black urban America, its culture, its politics, its militancy, its outrage against structural racism, and at the end of his life, a broad internationalist vision of emancipatory power far better than any other single individual, that he shared with DuBois and Paul Robeson, a pan-Africanist internationalist perspective. He shared with Marcus Garvey a commitment to building strong black institutions. He shared with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a commitment to peace and the freedom of racialized minorities. He was the first prominent American to attack and to criticize the U.S. role in Southeast Asia, and he came out four-square against the Vietnam War in 1964, long before the vast majority of Americans did. So that Malcolm X represents the cutting edge of a kind of critique of globalization in the 21st century. And in fact, Malcolm, if anything, was far ahead of the curve in so many ways. […]

Most people who read the autobiography perceive the narrative as a story that now millions of people know, and it was — it’s a story of human transformation, the powerful epiphany, Malcolm’s journey to Mecca, his renunciation of the Nation of Islam’s racial separatism, his embrace of universal humanity, of humanism that was articulated through Sunni Islam. Well, that’s the story everybody knows. But there’s a hidden history. You see, Malcolm and Haley collaborated to produce a magnificent narrative about the life of Malcolm X, but the two men had very different motives in coming together. Malcolm did — what Malcolm did not know is that back in 1962, a collaborator of Alex Haley, fellow named — a journalist named Alfred Balk had approached the FBI regarding an article that he and Haley were writing together for the Saturday Evening Post, and the FBI had an interest in castigating the Nation of Islam and isolating it from the mainstream of Negro civil rights activity. And so, consequently, a deal was struck between Balk, Haley and the FBI that the FBI provided information to Balk and Haley in the construction of their article, and Balk was — Balk was really the interlocutor between the FBI and the two writers in putting a spin on the article. The FBI was very happy with the article they produced, which was entitled “The Black Merchants of Hate,” that came out in early ’63. What’s significant about that piece is that that became the template for what evolved into the basic narrative structure of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. […]

One of the striking things about doing research on Malcolm X — and I believe that most Malcolm X researchers could tell you their own stories — is that there’s this paradox of the absence of critical information. Malcolm X is a person who has inspired — he has been the muse of several generations of black cultural workers, artists, poets, playwrights. There are literally a thousand works with the title “Malcolm X” in them. There are over 350 films and over 320 web-based educational resources with the title “Malcolm X,” yet the vast majority of them are based on secondary literatures, that is, not on primary source material. […]

*What is most interesting about the book is that, as I’ve read it over the years, something — something was odd to me. It’s like — you know, Malcolm broke with the NOI in March 1964, and in that last 11 chaotic months, he spent most of the time outside of the United States. Nevertheless, he built two organizations in the spring of 1964. First, Muslim Mosque Incorporated, which was a religious organization that was largely based on members of the NOI who left with him. It was spearheaded by James 67X, or James Shabazz, who was his chief of staff. And then secondly was the Organization of Afro-American Unity. This was an organization that was a secular group. It largely consisted of people that we would later call, several years later, Black Powerites, black nationalists, progressives coming out of the black freedom struggle, the northern students’ movement, people — students, young people, professionals, workers, who were dedicated to black activism and militancy, but outside of the context of Islam. There were tensions between these two organizations, and Malcolm had to negotiate between them, and since he was out of the country a great deal of the time, it was rather difficult for him to do so.

It seemed rather odd that there’s only a fleeting reference to the OAAU inside of the book that’s supposed to be his political testament. And I wondered about this. And it seemed like something was missing. Well, as a matter of fact, there is: three chapters. And those three chapters really represent a kind of political testament that are outlined by Malcolm X. And to make a long story short, they’re in a safe of a Detroit attorney by the name of Greg Reed. He purchased these chapters in a sale of the Haley Estate in late 1992 for the sum of $100,000. And since that time, no historian — or at least, I suppose, I’m the exception — very few people have actually had a chance to see the raw material that was going to comprise these three chapters: the missing political testament that should have been in the autobiography, but isn’t. […]

I could say that very few people have seen it. Reed, after a series of conversations — Reed said he would allow me to see this. This was about two years ago. I flew out to Detroit. I asked when could I come over to the office, and he said, “No, let’s meet at a restaurant,” which struck me as rather odd. We met at a restaurant. He came with a briefcase, and he opened the briefcase, and he showed me the manuscripts. And he said, “I’ll let you take a look at this for about 15 minutes.” Well, that wasn’t very much time, and I was deeply disappointed. Nevertheless, in that 15-minute time, looking at the content, because I’m so familiar with what Malcolm wrote at certain stages of his own life and development, it became very clear that there is a high probability he wrote this material sometime between August or September ’63 to about January ’64.

Now, this is a critical moment in his development. In November ’63, he gives his famous “Message to the Grassroots” address in Detroit, which really kind of marks off the real turning point in his own development. But I would argue that equally important is a brilliant address he gives in Harlem in mid-August of 1963, which actually is one of my favorite addresses by Malcolm, which actually is superior, in my judgment, to the “Message to the Grassroots” address, where he lays into a critique of what then is being mobilized, the march on Washington, D.C., the pinnacle of the civil rights movement. Malcolm envisions a broad-based pluralistic united front, which is spearheaded by the Nation of Islam, but mobilizing integrationist organizations, non-political organizations, civic groups, all under the banner of building black empowerment, human dignity, economic development, political mobilization. He’s already envisioning the NOI playing a role cooperatively with integrationist organizations. I believe that if we could see the chapters that are missing from the book, we would gain an understanding as to why, perhaps — perhaps — the FBI, the CIA, the New York Police Department and others in law enforcement greatly feared what Malcolm X was about, because he was trying to build a broad — an unprecedented black coalition across the lines of black nationalism and integration. And in a way, it presages 30 years ahead of time the Million Man March.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Malcolm X speaking a week before he was assassinated in 1965.

MALCOLM X: The police know the criminal operation of the Black Muslim movement, because they have thoroughly infiltrated it.

MANNING MARABLE: There were pivotal decisions that were made after this address. Malcolm met with the key members of the two organizations that he had established: Muslim Mosque Incorporated, MMI, which was largely a group of former Nation of Islam members who left the NOI out of loyalty to Malcolm; and second, OAAU, the Organization of Afro-American Unity, which was a secular organization of African American middle-class and working-class activists who joined Malcolm in building a more radical black nationalist movement in the mid-’60s.

The debate was, what do we do regarding the security of Malcolm X? The organization made two decisions that were highly contentious that evening: one, that none of Malcolm’s bodyguards, usually provided by Muslim Mosque Incorporated, would wear guns on the day of the big rally, which was scheduled on Sunday afternoon at the Audubon on the 21st of February; and secondly, no one would be searched, which actually was the standard protocol over the last several months at the Audubon, because Malcolm did not want to frighten off middle-class Negroes who were coming around and joining his movement.

But Malcolm’s own home had been firebombed the Sunday night before. I talked with James 67X Shabazz, who was Malcolm’s chief of staff, and others who eyewitnessed the assassination, and I challenged them personally and said, “How could you in good conscience have permitted Malcolm — even though he was the leader of the organization, nevertheless, there is a process of consultation. You were a his right-hand men and women. How could you have allowed him to do this?” And they said to me, “Brother Manning, you just didn’t know Brother Malcolm.” Then Malcolm insisted upon it.

So one of the riddles that I’m trying to solve in the autobiography is, why did Malcolm permit the context of the absence of security to occur on that particular day, especially at a time when the NYPD, the New York Police Department, and the FBI clearly set into motion decisions that facilitated the assassination on that day? […]

The assassination’s conspiracy is directly at odds with what the New York district attorney’s office came up with in the murder trial of 1966. According to the New York prosecutors and the NYPD, there were three people who were responsible for the murder of Malcolm X: Talmadge Hayer, Thomas Johnson and Norman Butler. These three men were affiliated with the Nation of Islam. They were prosecuted and convicted of first-degree murder. At the time, New York State did not have a death penalty. They were sent to prison for a quarter of a century.

It is very clear to me that Butler and Johnson were not at the Audubon that day of the assassination. Talmadge Hayer was. He was shot by Reuben Francis, the chief bodyguard of Malcolm X. But the circumstances of the murder and all of the evidence that we have points to six men, not three, who were involved in the assassination; that the assassination was carefully planned for weeks; that, indeed, the day before the Audubon rally that Malcolm X and the OAAU held, that there was a one-hour walkthrough that night of the killers.

And what’s curious were the actions of the NYPD and also the FBI. The NYPD ubiquitously followed Malcolm around wherever he spoke in the last year. They always had one to two dozen police officers. On this day, they pulled back the police guard. Many writers have already talked about this. But there were only two police officers in the Audubon at the time of the actual killing. And these two were assigned to the furthest end of the building, away from where the 400 people had gathered in the main ballroom. There were no cops outside. Usually, there were more than one or two dozen. So the police knew in advance something was going to occur that day.

JUAN GONZALEZ: That was the renowned African American historian Manning Marable, interviewed by Amy Goodman on May 21st, 2007, on Democracy Now!, and before that, on stunningnew”>[February 21], 2005. Marable passed away on Friday at the age of 60, three days before the publication of his book, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. To hear both interviews in their entirety, visit our website, democracynow.org. When we come back, we discuss Marable’s life’s work with Michael Eric Dyson and Bill Fletcher. Stay with us.

Media Options