Related

Guests

- Alice Walkeraward-winning author, poet and activist.

Links

- Part 2: Alice Walker on Activism, Gay Marriage, Angela Davis, Obama and Turning 70 Years Old

- "The World Will Follow Joy: Turning Madness into Flowers." By Alice Walker (The New Press)

- "Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth" Film Website

- Alice Walker’s Website

- "The Cushion in the Road: Meditation and Wandering as the Whole World Awakens to Being in Harm's Way." By Alice Walker (The New

Legendary author, poet and activist Alice Walker joins us to discuss her newest book, “The Cushion in the Road: Meditation and Wandering as the Whole World Awakens to Being in Harm’s Way,” in which she discusses many of the dominant themes in her life and work, including racism, Palestine, Africa and Obama’s presidency. The collection of essays explores Walker’s conflicting desire for deep engagement in the world and for a retreat into quiet contemplation. She has also just published a new collection of her poetry, “The World Will Follow Joy: Turning Madness into Flowers.” A film about her life, “Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth,” premieres this Friday in the United States. Walker also discusses the Obama administration’s recent addition of former Black Panther Assata Shakur to the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list 40 years after the killing for which she was convicted, her travels to the Eastern Congo, and the ongoing targeting of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Click here to see Part 2 of this interview.

Transcript

AARON MATÉ: We spend the rest of the hour with the legendary author, poet, activist, Alice Walker. In her newest book, The Cushion in the Road: Meditation and Wandering as the Whole World Awakens to Being in Harm’s Way, Alice Walker discusses many of the dominant themes in her life and work, including racism, activism, Palestine, Africa and President Obama. The collection of essays explores her conflicting desire for deep engagement in the world and for a retreat into quiet contemplation. Alice Walker is the first African-American woman to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. She won it in 1983 for her renowned novel The Color Purple, which also won the National Book Award for Fiction and was later adapted into a film and musical by the same name.

Alice Walker is also the subject of a new film that plays this Friday at the Seattle Film Festival and premiered in London on International Women’s Day in March. The film is called Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth and is directed by Pratibha Parmar. This is a clip from the trailer.

EVELYN WHITE: Alice claimed her space because she needed to be a writer. It saved her life in many regards.

DANNY GLOVER: Intrinsic in her writing is that part of her as a citizen, a citizen of the world, a woman, a woman of the world, and an activist.

ALICE WALKER: Three dollars cash

For a pair of catalog shoes

Was what the midwife charged

My mother

For bringing me.

“We wasn’t so country then,” says Mom,

“You being the last one —

And we couldn’t, like

We done

When she brought your

Brother,

Send her out to the

Pen

And let her pick

Out

A pig.”

JEWELLE GOMEZ: Whatever perspective you have, when you read her work, you know she’s talking to you. And the you in her writing is really quite universal.

HOWARD ZINN: It’s interesting. In her creative writing, she puts herself on a firing line, in that she is herself. She is not going to conform to any idea of what a black writer should do.

BEVERLY GUY-SHEFTALL: I don’t know any other black writer who has experienced the venom that she experienced from her own community, the community that she cares the most about.

AMY GOODMAN: From the trailer of the new film, Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth. You heard Evelyn White, Danny Glover, Jewelle Gomez, Howard Zinn, Beverly Guy-Sheftall. In addition to Alice Walker’s new book, The Cushion in the Road, a new collection of her poetry has just come out, The World Will Follow Joy: Turning Madness into Flowers.

Alice Walker, it’s great to have you back on Democracy Now! Congratulations on these two books. Talk first about The Cushion in the Road. What do you mean by that?

ALICE WALKER: Good morning. I mean that my life is so full of so much activity, and yet my heart—my heart and my soul are longing for my cushion, which is a meditation cushion, where I can contemplate. I can drop into the deep source of our lives and draw a lot of richness from that. And what I discovered, though, was that I would sit on my cushion in meditation, and I prepared a beautiful place just for that, and the phone would ring, and the world would call. And so, in some ways, I was very torn and conflicted, until I realized, by dreaming it, that at that part of my life when I was, you know, called to the world, my solution was to take my cushion with me on the road. And so that is what I have tried to do.

AARON MATÉ: Alice Walker, you began your activism when you joined the civil rights movement in Mississippi over 40 years ago. I’m wondering if you could talk about that experience and how it has informed your activism that still continues today?

ALICE WALKER: Well, actually, my activism started when I got on the—when I was leaving my home in Georgia on the Greyhound bus, and my dad took me to the bus stop. It was such a small town, there was no station, so the bus just stopped by the side of the road. I got on the bus, and feeling the joy and the emotion of the movement starting up in Alabama and Mississippi and other places, I sat in the front of the bus, and I was immediately forced back to the back of the bus. And I had to make a decision whether I would risk my education—I was 17—or whether I would keep on the bus and go to my first year of college and join the movement at my school. And this is what I did, and that was really the beginning of my activism. And years later, I went back to—I went to Mississippi and worked in the movement.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about—

ALICE WALKER: And how does it—

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead, Alice.

ALICE WALKER: Now, how does it inform my activism? Well, I see myself in all the people in the world who are suffering and who are very badly treated and who are often made to feel that they have no place on this Earth. And this Earth actually belongs to all of us. The universe belongs to all of us. And we mustn’t forget it, you know. And I know firsthand how it feels when people tell you and make you think that, you know, they can have everything, they can have as much as they want, they can buy everything they desire, and you are supposed to have nothing. Well, this is not—it’s not right, and we must not accept it.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about Assata Shakur, who you’ve also written about recently. Earlier this month, the FBI added the former Black Panther to its Most Wanted Terrorists list, 40 years after the killing for which she was convicted. She became the first woman added to the list, and the reward for her capture was doubled to $2 million. This is a clip from the film Eyes of the Rainbow: The Assata Shakur Documentary, when she talks about her experience in prison.

ASSATA SHAKUR: Prisons are big business in the United States, and the building, running and supplying of prisons has become the fastest-growing industry in the country. Factories are moving into the prisons, and prisoners are forced to work for slave wages. This super-exploitation of human beings has meant the institutionalization of a new form of slavery. Those who cannot find work on the streets are forced to work in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Assata Shakur, and that’s from Eyes of the Rainbow. Alice Walker, after the roadside shooting in which Assata Shakur was severely wounded, and she went to trial and was convicted, a crime she says she didn’t commit, she escaped from prison and got political asylum in Cuba, where she has lived for decades. Your thoughts on what has most recently happened, her being added to the terrorists list?

ALICE WALKER: Well, I see it as an attack, really, a sort of covert sneaky attack on Cuba. I think that the governments, all of them, in recent memory, have wanted to destroy the Cuban people, really, and their insistence on their freedom and their dignity. And I think this is a way of saying that, you know, you have a, quote, “terrorist” there, and we have a right to go in and get her. And so, this could cause a very big fight between these countries, which have never had peace in my lifetime.

AMY GOODMAN: You dedicated The Cushion in the Road: Meditation and Wandering as the Whole World Awakens to Being in Harm’s Way to Celia Sánchez Manduley and Fidel Castro Ruz. You say, “revolutionaries, teachers and spiritual guides who were, as well, one of the most inspiring power couples of the 20th century.” Why this dedication?

ALICE WALKER: Well, because they were. It’s just that we didn’t know anything about it. I think if you said to almost any North American, “Who was Celia Sánchez Manduley?” they wouldn’t have a clue. They wouldn’t know. And I didn’t know, actually, very much. But she and Fidel had this partnership and actually were co-revolutionaries together. And she was very prominent in the leadership of the Cuban revolution. And there’s a new book about her called One Day in December by Nancy Stout. It’s the life of Celia Sánchez. And this is a woman who can teach a lot of us about what it feels like and what it can be like to come face to face with the reality that your country is being not only stolen from you, but trashed, absolutely degraded—you know, your mountains despoiled, your rivers a mess, your children badly educated, if educated at all. So this book, I think, is crucial for people to have a guide, especially women, but also men, of course, a guide to see what it’s like to actually confront, you know, the forces that are literally destroying you, they’re destroying your children—horrible food, horrible laws, you know, rich people permitted to own much more than anyone should own of anything, and poor people being continually ground into the dust.

AARON MATÉ: Alice Walker, I want to ask about your travels. You’ve gone to Gaza. You’ve gone to Rwanda and eastern Congo. Can you talk about these experiences and what they left you with?

ALICE WALKER: Well, the Congo was the hardest, because there I saw that people will just do anything for gold and silver and coltan and whatever they can get, and that they care absolutely nothing about the suffering of the people. As you know, the Congo is called the worst place on the planet to be if you’re a woman. And I saw that in action. I saw the result of so much horrible atrocity in that place. But this is something that people should be very aware of in places where this kind of atrocity is not yet happening, because this is—you know, it’s crucial to see ourselves always as a part of whatever is going on, because we are. You know, this is one planet, and we are one people. And we learn from each other. We learn the awful things just as clearly as we learn the good things. And so, if you want to see what is a possibility for a really dreadful future, even here, go to the Congo and to places where, you know, people are fighting over minerals and resources that actually the people who live there will never benefit from.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve also been to Burma, and you write about Aung San Suu Kyi.

ALICE WALKER: Well, I went to Burma before she was freed from house arrest. And we actually went and tried to get our cab driver to stop in front of her gate so we could just, you know, sort of bear witness, but he was so afraid, that he couldn’t stop, and he was—you know, sort of wanted us to get out of his cab because we put him in danger. But now she is out, of course. And, actually, once she was freed from her house arrest and she started talking to the world herself, I haven’t really kept up. You know, I feel that she’s such an amazing being, and she’s so smart, and she has a good heart, and she’s a practiced meditator, which I think is of value, because it means that her thinking is the kind of thinking that understands that the harm that you do to others is the harm that you do to yourself. And you cannot think, then, that you can cause wars in other parts of the world and destroy people and drone them, without this having a terrible impact on your own soul and your own consciousness.

AMY GOODMAN: Alice, your book of poetry, The World Will Follow Joy: Turning Madness into Flowers, could you read a poem from it?

ALICE WALKER: I would love to. This is a poem called “Coming to Worship the 1000 Year Old Cherry Tree.” And the preface to that is that I was in Japan at some point years ago for the Tokyo Book Fair, and I knew it was going to be a lot of work, and they did, too. And they, the people who invited me, insisted that not only could they take me to the countryside to have, you know, a wonderful bath and a beautiful place, you know, a massage, but they also wanted me to see this thousand-year-old cherry tree, which reminds us—this kind of old, beautiful tree reminds us of how long humans have been here and how much we have loved this planet. So, this poem is a result of going to see this wonder, this incredibly beautiful cherry tree in full blossom.

Life is good. Goodness is its character;

all else is defamation.

The Earth is good. Goodness is its nature.

Nature is good. Goodness is its essence.

People are also good. Goodness is our offering;

our predictable yet unfathomable flowering.

Thankful and encouraged

Infused with our peaceful inheritance,

Our peaceful inheritance,

May we not despair.

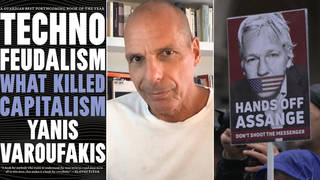

AMY GOODMAN: Alice Walker, reading from The World Will Follow Joy, her poem “”Coming to Worship the 1000 Year Old Cherry Tree.” Alice, tomorrow on Democracy Now! we will be interviewing Julian Assange from his, in a sense, cell. He has taken refuge in the Ecuadorean embassy in London. He is the WikiLeaks founder. And I was wondering if you have a message for him or a message for people in this country about Julian Assange. What do you think of WikiLeaks and his predicament right now?

ALICE WALKER: I think unless the people are given information about what is happening to them, they will die in ignorance. And I think that’s a big sin. I mean, if there is such a thing as a sin, that’s it, to destroy people and not have them have a clue about how this is happening. So I think that when people like Assange step up to this place of sharing knowledge about what is happening, I think it’s an honorable place. I know that there have been charges against him for, you know, other things, but personally, I would have to be convinced. And looking at just what he has given us in terms of sharing information that can help us, I think he’s very heroic.

AMY GOODMAN: Alice Walker—

ALICE WALKER: And I think that we should support him.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there, but we do part two post-show. Go to our website at democracynow.org. Alice Walker, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

Media Options