Related

Topics

Guests

- Joyce Hormanwidow of journalist and human rights activist Charles Horman, who was disappeared and killed in Chile soon after the 1973 coup. His story was the focus of the movie Missing. Joyce filed a criminal suit against Pinochet in 2000 and established the Charles Horman Truth Foundation to support ongoing investigations into the human rights violations during Pinochet’s regime.

- Peter Weissvice president of the board of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He represented the Horman family in their case against Kissinger and others for the death of Charles Horman.

As we continue our look at the 40th anniversary of the U.S.-backed military coup in Chile and the ongoing efforts by the loved ones of its victims to seek justice, we turn to the case of Charles Horman. A 31-year-old American journalist and filmmaker, Horman was in Chile during the coup and wrote about U.S. involvement in overthrowing the democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. Shortly after, he was abducted by Chilean soldiers and later killed. Horman’s story was told in the 1982 Oscar-nominated film, “Missing,” which follows his father, Edmund Horman, going to Chile to search for his son. We’re joined by Charles Horman’s widow, Joyce Horman, who filed a criminal suit against Pinochet for his role in her husband’s death, and established the Charles Horman Truth Project to support ongoing investigations into human rights violations during Pinochet’s regime. We’re also joined by Peter Weiss, vice president of the board of the Center for Constitutional Rights, who represented the Horman family in their case against Kissinger and others for Charles Horman’s death.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: As we continue to mark this 40th anniversary this week of the U.S.-backed military coup in Chile—it was September 11th, 1973—today, the loved ones of thousands who were killed under General Pinochet’s dictatorship continue to seek justice. We turn now to the case of Charles Horman, 31-year-old American freelance journalist and filmmaker who was in Chile during the coup and wrote about the U.S. involvement in overthrowing Allende. Soon afterward, he was abducted by Chilean soldiers, later killed.

The story of what happened next is told in the 1982 Oscar-nominated film, Missing, which follows his father, Ed Horman, when he goes to Chile amidst the bloodshed of the coup to join his daughter-in-law, who in the film is played by Sissy Spacek, in the search for the son. This is a clip from the film when we see Ed Horman, played by Jack Lemmon, meeting with U.S. officials in Chile as a photo of then-President Richard Nixon hangs on the wall behind them. Horman went to Chile knowing that soldiers had seized Charles, but unaware that he had been shot to death at that point.

U.S. AMBASSADOR: [played by Richard Venture] I hear you’d like to discuss some political questions.

ED HORMAN: [played by Jack Lemmon] What?

U.S. AMBASSADOR: [played by Richard Venture] You suggested that there might be some kind of American police assistance program down here? I’d like you to know that nothing of that sort exists in this country.

ED HORMAN: [played by Jack Lemmon] Mr. Ambassador, I’m not interested in the politics of it, and I brought it up only because I want you to use every resource at your command.

U.S. AMBASSADOR: [played by Richard Venture] I repeat, Mr. Horman, no such operation exists.

CONSUL PHIL PUTNAM: [played by David Clennon] I got the clearance for those hospitals you wanted to visit.

ED HORMAN: [played by Jack Lemmon] What about the National Stadium?

CONSUL PHIL PUTNAM: [played by David Clennon] I’m trying, but it’s kinda touchy.

U.S. AMBASSADOR: [played by Richard Venture] Handle it.

ED HORMAN: [played by Jack Lemmon] What do you mean it’s touchy? Look, gentlemen, I know these are bad times. It’s not fun for you people. It’s certainly not fun for Beth or me—or Charles. I know you’re doing your best. I have to believe that; that’s our only hope. But you have all the machinery on your side. Don’t you see? You have all the connections. I’m a middle-aged businessman from New York City. I don’t speak one word of Spanish. Here I am. My son may have been shot. Maybe he was tortured. Maybe he was—oh, Lord, beaten so badly that they’re keeping him until he’s well enough to be released. I don’t know. I don’t care. Oh, really, I don’t care, because what is done is done. I just want you to reach those people and tell them I will take Charles back in any condition. I’m not going to make a stink. I’m not going to go to the newspapers. You make out any kind of a release form; I will sign it. I will absolve anyone, everyone, of everything. I just want my boy back. He’s the only child I have, sir.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from the 1982 film Missing, about the struggle to discover what happened to journalist Charlie Horman during the 1973 Chilean coup. Jack Lemmon plays Horman’s father, Ed Horman.

Well, today we’re joined by Charlie Horman’s widow, Joyce Horman. She filed a criminal suit against Pinochet for his role in her husband’s death, and established the Charles Horman Truth Project to support ongoing investigations into the human rights violations during Pinochet’s regime. And it’s her foundation that has gathered people from around the world involved in trying to bring Augusto Pinochet to justice, from Chile to London, where he was arrested, to finding the killers of the many people. Thousands of Chileans died under the 17-year reign of Augusto Pinochet. And some of those who have been fighting for justice are gathering tonight for an event to remember what took place 40 years ago.

Joyce Horman, welcome to Democracy Now!

JOYCE HORMAN: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Missing certainly made your husband famous throughout the United States, that film by Costa-Gavras, but also showed that Charlie, though, was an American. It was thousands of Chileans who were killed in those years under Pinochet. Talk about the day that your husband was taken. You both were living in Santiago?

JOYCE HORMAN: We were living in Santiago. And he had just managed to get back from Viña del Mar, where he had taken a friend of ours from New York right before the coup and was trapped there for five days. So, he returned on Sunday, and then, Monday, he was going to go and find out about airplane tickets downtown. The curfew had been lifted during the day. So he and our friend, Terry, went down to the center of Santiago to look for tickets or a way out.

AMY GOODMAN: What did he see, where he was?

JOYCE HORMAN: Where he was, well, he saw American battleships off the shore. He saw the launch of the coup in Viña del Mar. They experienced that all the roads had been blocked and the trains had been stopped that night, Monday night before the coup, which is why he knew that was happening. But he also—he also met, in the hotel that they stayed, military—U.S. military people who were taking quite a large credit for the coup and were very excited about the success. And my husband, the journalist, knew that that was not something that anybody in the United States knew about. So, he was aware that it was incredible information at that point.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, he comes back to Santiago, to the capital of Chile. You see each other on the morning of the coup.

JOYCE HORMAN: Yes, I guess I have to start back. He was brought back to Santiago, to the search-and-destroy mission that was Santiago at that time, by the head of the U.S. MILGROUP, Military Group, who had come through blockades to get to Viña del Mar to see his military people in Viña, and then, because they had asked him if he would give a lift to Charles and Terry back to Santiago. His name is Ray, Captain Ray Davis, and he is an extraordinary figure in our story, and the extradition request for him was issued—well, was approved by the Chilean Supreme Court recently. But let me go back. So, he’s the one who went—again, drove through all the roadblocks, because he had all of the connections with the Pinochet forces, and brought them back to Santiago, dropped them in Santiago on Saturday. They came home on Sunday. I’m sorry, I think I lost the line of your original question.

AMY GOODMAN: What you were doing that day, when you last saw him, and then how he was taken—

JOYCE HORMAN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —how you learned he was taken.

JOYCE HORMAN: OK. We said goodbye as I was leaving to check on some other friends to be sure that they were OK, because there was very little communication for a week, and he was taking our friend Terry downtown to try and get a passage out. I did not get back that night because of the curfew. The buses stopped running. And as the movie Missing portrays, I was in a stairwell for the night.

When I got back to the house the next morning, I found the house completely ransacked. And my neighbors told me to go elsewhere, because the police—or the military people that had taken my husband would probably come back. Only they didn’t say they had taken my husband. They just said they had been there and ransacked the place, so I wasn’t sure that my husband had gotten back that night.

I guess it was the next day, neighbors from our old neighborhood got a call from the military intelligence saying, “Do you know—do you know an extremist gringo with a beard?” And it terrified our neighbors, but it told us that the military actually had Charles. And the next opportunity I had, I went to the consulate and the—the embassy, actually, to announce that he had been taken and that I wanted their help to find him and get him out. They were more interested in what had been taken from the house, the ransacked house. But that was the first contact I had with the U.S. officials at that point.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to jump forward a little bit and go back to the film Missing, and this is where we see, well, your character is called Beth in the film—that’s what you chose; you weren’t sure if this was going to be a film you wanted to be any part of.

JOYCE HORMAN: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: And you are played by Sissy Spacek, to this day who’s very—you are tied to and is very close to this story.

JOYCE HORMAN: Mm-hmm.

AMY GOODMAN: She and Jack Lemmon, who plays your father-in-law, Charlie’s father Ed, go to the stadium, where they’re allowed to get on the loudspeaker and ask if Charlie is there. Thousands of sympathizers of the ousted Socialist President Salvador Allende were rounded up and taken to the stadium in the days following September 11, 1973, the coup.

BETH HORMAN: [played by Sissy Spacek] Charlie? This is Beth. I’m here with your dad, Charlie, and the American consul. So if you can hear me, please come out so we can take you home.

ED HORMAN: [played by Jack Lemmon] Charles Horman, this is your father, Edmund. I’m here in the hope that you can hear me. Charles? Charles? Do you remember when we took that trip together across country from L.A. to New York? Just the two of us.

AMY GOODMAN: A clip from the 1982 Costa-Gavras film, Missing, about Charlie Horman, one of thousands of people, as Augusto Pinochet came to power and over the 17 years of his reign, who went missing and were killed. This is Democracy Now! We’ll continue this discussion after we listen to more of Víctor Jara.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Plegaria [a] un Labrador (Prayer to a Worker)” by Víctor Jara, the Chilean singer-songwriter, folk singer, tortured and executed during the Chilean coup of Salvador Allende 40 years ago this week, September 11, 1973, as we honor this 40th anniversary of all those lost. We go—you can go to our website at democracynow.org to see the timeline of all of our coverage over these years.

We continue our coverage of the 40th anniversary as we’re joined by Joyce Horman, Charles Horman’s widow. She established the Charles Horman Truth Project to support ongoing investigations into the human rights violations during Pinochet’s regime.

We’re also joined by Peter Weiss, vice president of the board of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He represented the Horman family in their case against Henry Kissinger and others for the death of Charles Horman. This afternoon and this evening, there will be a major gathering at—in New York City as people gather from around the world to honor those who died during these days 40 years ago. At 583 Park Avenue, there will be a forum and discussion and panels—that is, run by the Charles Horman Truth Foundation.

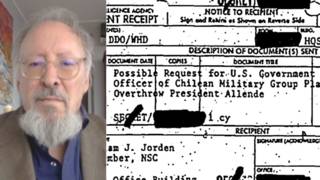

I want to read part of a declassified transcript of a conversation just one day before Charles Horman was seized between then-President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. When discussing the U.S. role in the Chilean coup, Kissinger said, quote, “The Chilean thing is getting consolidated.” Nixon responded, “Well, we didn’t—as you know—our hand doesn’t show on this one, though.” Kissinger replied, “We didn’t do it. … I mean we helped them. [Omitted word] created the conditions as great as possible.” And Nixon responded, “That is right.” The two then discussed, quote, “this crap from the liberals” in the media about the overthrow of a democratically elected government, and Kissinger noted, “In the Eisenhower period … we would be heroes.” Now, that is taken from a declassified memo that was declassified for the National Security Archive. It appears in the new edition of a new book that has come out by Peter Kornbluh on Pinochet and these years and is also cited in the—in Peter Kornbluh’s latest piece in The Nation magazine.

Peter Weiss, their role of Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon in Allende coup?

PETER WEISS: Well, they were responsible for the coup, because they decided as soon as Salvador Allende, who was a Socialist, became president of Chile, that he had to go. And Chile was not the only country where the United States then was deciding that people had to go. And Kissinger was eventually put in charge of the 40 Committee, which was given such a nondescript name because one couldn’t say what it was actually about. But it was about preparing the coup. And the coup had two tracks, essentially. It had track one, which was managed by the State Department, more or less overtly. And then it had track two, managed by the CIA, entirely covertly. And Nixon allocated $10 million to the CIA to prepare for the coup, to mobilize, to have a relationship between the corporations that were interested in getting rid of Allende, and it was also supposed to activate the media. And it worked, as you said when you quoted Nixon and Kissinger saying, “We did it, but we didn’t do it.”

AMY GOODMAN: I want to read from a declassified U.S. State Department memo on the Charles Horman case dated August 25th, 1973. It says, quote, “There is some circumstantial evidence to suggest US intelligence may have played an unfortunate part in Horman’s death. At best, it was limited to providing or confirming information that helped motivate his murder by the [government of Chile, or] GOC. At worst, US intelligence was aware that GOC saw Horman in a rather serious light and US officials did nothing to discourage the logical outcome of GOC [government of Chile] paranoia.”

PETER WEISS: Well, there were actually two ways in which Charles Horman was failed by his government. One was that they helped to orchestrate the coup, and the other was that they didn’t lift a finger to get him out of Chile when they had every reason to believe that he was in great danger. And there is an international law, an obligation, for governments to keep their citizens from being killed in foreign countries. The United States completely failed to do anything about that.

AMY GOODMAN: Kissinger is still alive. President Nixon of course has died. The case was dismissed, Joyce and Peter, against Kissinger. Why? And are there cases now that involve him?

PETER WEISS: I’m not aware of any pending cases now. Maybe Almudena knows of some, but I’m not aware of any pending cases. Our case was dismissed because we couldn’t conduct discovery. When you bring any kind of case, civil or criminal, you have to look for the evidence and produce the evidence to the judge or the jury. And everything that we wanted, we were told, was classified and would not be made available to us. So, eventually, the case had to be dismissed, because we couldn’t establish the causal relationship between Charles’s death and what people like Ray Davis, whom Joyce mentioned, who was the head of the—

JOYCE HORMAN: Military Group.

AMY GOODMAN: MILGROUP.

PETER WEISS: —of the Military Group at the embassy—

AMY GOODMAN: In this last minute, as you mention international law, it’s being invoked a lot these days as we look at the possible strike against Syria. Peter Weiss, you are legendary in your defense of international law. What are the parallels you see?

PETER WEISS: I see two parallels. One is that the Assad regime engaged in multitudinous violations of international law for two-and-a-half years. Right? I mean, they bombed. They sent artillery rockets into civilian areas, which is a cardinal violation of international law. And nobody really mentioned the fact that these were international law violations. And then come the chemical weapons, and everybody is saying, “Oh, my god, you know, now they’ve violated international law.” What were they doing before? Complying with international law? Surely not. So, that’s one thing.

The other thing is that if—

AMY GOODMAN: We have 15 seconds.

PETER WEISS: —Obama decides to go in there without approval from the international community, he will be guilty of a tremendous violation of international law. And you can’t uphold international law by violating international law.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to continue the discussion both on Syria as well as on this 40th anniversary of the coup in Chile tomorrow on Democracy Now!

Media Options